Citado por: 1

Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, and Steven Izenour, 1977 [1972]:

"The first part of this book is a description of our study of the architecture of the commercial strip. Part II is a generalization on symbolism in architecture and the iconography of urban sprawl from our findings in Part I.

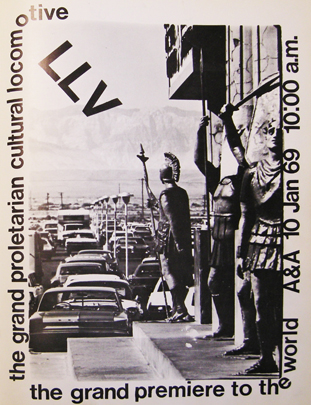

‘Passing through Las Vegas is Route 91, the archetype of the commercial strip, the phenomenon at its purest and most intense. We believe a careful documentation and analysis of its physical form is as important to architects and urbanists today as were the studies of medieval Europe and ancient Rome and Greece to earlier generations. Such a study will help to define a new type of urban form emerging in America and Europe, radically different from that we have known; one that we have been ill-equipped to deal with and, from ignorance, we define today as urban sprawl. An aim of this studio will be, through open-minded and nonjudgmental investigation, to come to understand this new form and to begin to evolve techniques for its handling.'"

PART I

A SIGNIFICANCE FOR A&P PARKING LOTS, OR LEARNING FROM LAS VEGAS

"Learning from the existing landscape is a way of being revolutionary for an architect. Not the obvious way, which is to tear down Paris and begin again, as Le Corbusier suggested in the 1920s, but another, more tolerant way; that is, to question how we look at things."

"Las Vegas is analyzed here only as a phenomenon of architectural communication. Just as an analysis of the structure of a Gothic cathedral need not include a debate on the morality of medieval religion, so Las Vegas's values are not questioned here. The morality of commercial advertising, gambling interests, and the competitive instinct is not at issue here, although, indeed, we believe it should be in the architect's broader, synthetic tasks of which an analysis such as this is but one aspect. The analysis of a drive-in church in this context would match that of a drive-in restaurant, because this is a study of method, not content. [...]"

PART II

UGLY AND ORDINARY ARCHITECTURE, OR THE DECORATED SHED

"We shall emphasize images - image over process or form - in asserting that architecture depends in its perception and creation on past experience and emotional association and that these symbolical and representational elements may often be contradictory to the form, structure, and program with which they combine in the same building. We shall survey this contradiction in its two main manifestations:

1. Where the architectural systems of space, structure, and program are submerged and distorted by an overall symbolic form. This kind of building-becoming-sculpture we call the duck in honor of the duck-shaped drive in, ‘The Long Island Duckling,' illustrated in God's Own Junkyard by Peter Blake [...].

2. Where systems of space and structure are directly at the service of the program, and ornament is applied independently of them. This we call the decorated shed [...].

The duck is the special building that is a symbol; the decorated shed is the conventional shelter that applies symbols [...]. We maintain that both kinds of architecture are valid - Chartres is a duck (although it is a decorated shed as well), and the Palazzo Farnese is a decorated shed - but we think that the duck is seldom relevant today, although it pervades Modern architecture."

VENTURI, Robert; SCOTT BROWN, Denise; IZENOUR, Steven. Learning from Las Vegas: the forgotten symbolism of architectural form. 2. ed. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977, grifos dos autores.

"This new edition of Learning from Las Vegas arose from the displeasure expressed by students and others at the price of the original version. [...]

The main omissions are the final section, on our work, and about one-third of the illustrations, including almost all in color and those in black and white that could not be reduced to fit a smaller page size. Changes in format further reduce costs, but we hope that they will serve too, to shift the book's emphasis from illustrations to text, and to remove the conflict between our critique of Bauhaus design and the latter-day Bauhaus design of the book; the ‘interesting' Modern styling of the first edition, we felt, belied our subject matter, and the triple spacing of the lines made the text hard to read.

Stripped and newly clothed, the analyses of Part I and the theories of Part II should appear more clearly what we intended them to be: a treatise on symbolism in architecture. Las Vegas is not the subject of our book. The symbolism of architectural form is. Most alterations to the text (aside from corrections of errors and changes to suit the new format) are made to point up this focus. For the same reason we have added a subtitle, The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form. A few more changes were made, elegantly, we hope, to ‘de-sex' the text. Following the saner, more humane custody of today, the architect is no longer referred to as ‘he.'"

SCOTT BROWN, Denise. Preface to the revised edition. In: VENTURI, Robert; SCOTT BROWN, Denise; IZENOUR, Steven. Learning from Las Vegas: the forgotten symbolism of architectural form. 2. ed. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1977. p. XV-XVII, grifos da autora.

"With the publication in 1972 of Learning from Las Vegas, written by Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steve Izenour, Venturi's sensitive and sane assessment of the cultural realities confronting everyday practice - the need to set order against disorder and vice versa - shifted from an acceptance of honky-tonk to its glorification; from a modest appraisal of Main Street as being ‘almost alright' to a reading of billboard strip as the transmogrified utopia of the Enlightenment, lying there like a science-fiction transposition in the midst of the desert!

This rhetoric, which would have us see A & P parking lots as the tapis verts of Versailles, or Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas as the moder equivalent of Hadrian's Villa, is ideology in its purest form. The ambivalent manner in which Venturi and Scott-Brown exploit this ideology as a way of bringing us to condone the ruthless kitsch of Las Vegas, as an exemplary mask for the concealment of the brutality of our own environment, testifies to the aestheticizing intent of their thesis. And while their critical distance permits them the luxury of describing the typical casino as a ruthless landscape of seduction and control - they emphasize the two-way mirrors and the boundless, dark, and disorientating timelessness of its interior - they take care to disassociate themselves from its values. This does not prevent them, however, from positing it as a model for the restructuring of urban form [...]"

FRAMPTON, Kenneth. Modern architecture: a critical history. Londres: Thames & Hudson, 1980, grifos do autor.

"[...] In A Significance for A&P Parking Lots, or Learning from Las Vegas and ‘Learning from Levittown' he and his collaborators, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, told where the necessary ‘messy vitality' might be found. Its cues would come from the ‘vernacular' architecture of America in the second half of the twentieth century. ‘Main Street is almost all right,' according to one of his dicta. So were the housing developments (Levittown) and the commercial strips (Las Vegas)."

"Not for a moment did Venturi dispute the underlying assumptions of modern architecture: namely, that it was to be for the people; that it should be nonbourgeois and have no applied decoration; that there was a historical inevitability to the forms that should be used; and that the architect, from his vantage point inside the compound, would decide what was best for the people and what they inevitably should have."

"In the Venturi cosmology, the people could no longer be thought of in terms of the industrial proletariat, the workers with raised fists, engorged brachial arteries, and necks wider than their heads, Marxism's downtrodden masses in the urban slums. The people were now the ‘middle-middle class,' as Venturi called them. They lived in suburban developments like Levittown, shopped at the A & P over in the shopping center, and went to Las Vegas on their vacations the way they used to go to Coney Island. The middle-middle folk were not the bourgeoisie. They were the ‘sprawling' masses, as opposed to the huddled ones. To act snobbishly toward them was to be elitist. And what could be more elitist in this new age, Venturi wanted to know, than the Mies tradition of the International Style, with its emphasis on ‘heroic and original' forms? Mies' modernism had itself... gone bourgeois! Modern architects had become obsessed with pure form. He compared the Mies box to a roadside stand in Long Island built in the shape of a duck. The entire building was devoted to expressing a single thought: ‘Ducks in here.' Likewise, the Mies box: It was nothing more than a single expression: ‘Modern architecture in here.' Which made it expressionism, right? Heroic, original, elitist, expressionist - how very bourgeois!"

WOLFE, Tom. From Bauhaus to our house. Nova York: Washington Square, 1981, grifos do autor.

"One of the most telling documents of the break of postmodernism with the modernist dogma is a book coauthored by Robert Venturi, Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour and entitled Learning from Las Vegas. Rereading this book and earlier writings by Venturi from the 1960s today, one is struck by the proximity of Venturi's strategies and solutions to the pop sensibility of those years. Time and again the authors use pop art's break with the austere canon of high modernist painting and pop's uncritical espousal of the commercial vernacular of consumer culture as an inspiration for their work. What Madison Avenue was for Andy Warhol, what the comics and the Western were for Leslie Fiedler, the landscape of Las Vegas was for Venturi and his group. The rhetoric of Learning from Las Vegas is predicated on the glorification of the billboard strip and of the ruthless shlock of casino culture. In Kenneth Frampton's ironic words, it offers a reading of Las Vegas as ‘an authentic outburst of popular phantasy.' I think it would be gratuitous to ridicule such odd notions of cultural populism today. While there is something patently absurd about such pro-positions, we have to acknowledge the pwoer [sic] they mustered to explode the reified dogmas of modernism and to reopen a set of questions which the modernism gospel of the 1940s and 1950s had largely blocked from view: questions of ornament and metaphor in architecture, of figuration and realism in painting, of story and representation in literature, of the body in music and theater. Pop in the broadest sense was the context in which a notion of the postmodern first took shape, and from the beginning until today, the most significant trends within postmodernism have challenged modernism's relentless hostility to mass culture."

HUYSSEN, Andreas. Mapping the Postmodern. New German Critique, Durham, n. 33, "Modernity and Postmodernity", p. 5-52, Autumn 1984, grifos do autor.

"The Venturi Team would exclude a whole repertoire of codes, not only ‘ducks', but also ‘Heroic and Original' architecture, the grand gesture, the revival of the palazzo pubblico, and all the work they conceive in opposition to their decorated sheds. Why? Because they still keep a modernist notion of the Zeitgeist, and their particular spirit of the age ‘is not the environment for heroic communication through pure architecture. Each medium has its day'; our day, you might have heard from McLuhan, is one of the symbolism via the electronic media - the ‘electrographic architecture' of Tom Wolfe. It's amusing to note the symmetrically opposite positions of Team Venturi and Philip Johnson. They both take a priori stands on ‘pure' form - one anti, one pro - as if such one-sided views of communication were adequate. Since Post-Modernism is radically inclusivist (like Renaiscance architecture) it must fault the oversimplification of both polemicist and attack its causes. [...]

The Venturi Team have definitely responded to several codes which have heretofore remained unserviced by architects, those coming from the lower middle class and the commerce of Route 66. Their actual buildings, however, have usually been for a different taste culture - for professors or colleges, or ‘tasteful clients' - thus creating a kind of hiccup between theory and practice."

JENCKS, Charles. The language of post-modern architecture. 4. ed. Nova York: Rizzoli, 1984, grifos do autor.

"From the aesthetics of the appearance of stable images, present precisely because of their static nature, to the aesthetics of the disappearance of unstable images, present because of their motion (cinematic, cinemagraphic), a transmutation of representations has taken place. The emergence of form and volume intended to exist as long as their physical material would allow has been replaced by images whose only duration is one of retinal persistence. Ultimately, it seems that Hollywood, much more than Venturi's Las Vegas, merits a study of urbanism, since, after the theaters of antiquity and the Italian Renaissance, it was the first Cinecittŕ: the city of living cinema where sets and reality, cadastral urban planning and cinematic footage planning, the living and the living dead merge to the point of delirium. Here, more than anywhere, advanced technologies have converged to create a synthetic space-time. The Babylon of film ‘derealization,' the industrial zone of pretense, Hollywood built itself up neighborhood by neighborhood, avenue by avenue, upon the twilight of appearances, the success of illusions and the rise of spectacular productions (such as those of D. W. Griffith) while waiting for the megalomaniac urbanization of Disneyland, Disneyworld and Epcot Center.

When Francis Ford Coppola directed One From the Heart by inlaying his actors, by an electronic process, in the filmic framework of a life-sized Las Vegas reconstructed in Zoetrope Company Studios simply because he did not want his shooting to adapt itself to the city, but for the city to adapt itself to his shooting, he surpassed Venturi by far, not so much by demonstrating contemporary architectural ambiguity but by showing the ‘spectral' character of the city and its inhabitants."

VIRILIO, Paul. The overexposed city. Zone, Nova York, n. 1-2, p. 14-31, 1986, grifo do autor.

"With respect to architecture, for example, Charles Jencks dates the symbolic end of modernism and the passage to the postmodern as 3.32 p.m. on 1 5 July 1972, when the Pruitt-Igoe housing development in St Louis (a prize-winning version of Le Corbusier's ‘machine for modern living') was dynamited as an uninhabitable environment for the low-income people it housed. Thereafter, the ideas of the ClAM, Le Corbusier, and the other apostles of ‘high modernism' increasingly gave way before an onslaught of diverse possibilities, of which those set forth in the influential Learning from Las Vegas by Venturi, Scott Brown, and Izenour (also published in 1972) proved to be but one powerful cutting edge. The point of that work, as its title implies, was to insist that architects had more to learn from the study of popular and vernacular landscapes (such as those of suburbs and commercial strips) than from the pursuit of some abstract, theoretical, and doctrinaire ideals. It was time, they said, to build for people rather than for Man. [...]"

"Venturi et al. [in Learning from Las Vegas] recommend that we learn our architectural aesthetics from the Las Vegas strip or from much-maligned suburbs like Levittown, simply because people evidently like such environments. ‘One does not have to agree with hard hat politics,' they go on to say, ‘to support the rights of the middle-middle class to their own architectural aesthetics, and we have found that Levittown-type aesthetics are shared by most members of the middle-middle class, black as well as white, liberal as well as conservative.' There is absolutely nothing wrong, they insist, with giving people what they want, and Venturi himself was even quoted in the New York Times (22 October 1972), in an article fittingly entitled ‘Mickey Mouse teaches the architects,' saying ‘Disney World is nearer to what people want than what architects have ever given them.' Disneyland, he asserts, is ‘the symbolic American utopia.'"

HARVEY, David. The condition of Postmodernity: an enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Cambridge; Oxford: Blackwell, 1990, grifos do autor.

"Postmodernism in architecture will then logically enough stage itself as a kind of aesthetic populism, as the very title of Venturi's influential manifesto, Learning from Las Vegas, suggests. However we may ultimately wish to evaluate this populist rhetoric, it has at least the merit of drawing our attention to one fundamental feature of all the postmodernisms enumerated above: namely, the effacement in them of the older (essentially high-modernist) frontier between high culture and so-called mass or; commercial culture, and the emergence of new kinds of texts infused with the forms, categories and contents of that very culture industry so passionately denounced by all the ideologues of the modern, from Leavis and the American New Criticism all the way to Adorno and the Frankfurt School. The postmodernisms have, in fact, been fascinated precisely by this whole ‘degraded' landscape of schlock and kitsch, of TV series and Reader's Digest culture, of advertising and motels, of the late show and the grade-B Hollywood film, of so-called paraliterature, with its airport paperback categories of the gothic and the romance, the popular biography, the murder mystery, and the science fiction or fantasy novel: materials they no longer simply ‘quote,' as a Joyce or a Mahler might have done, but incorporate into their very substance."

JAMESON, Fredric. Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991, grifos do autor.

"Revisiting Las Vegas by invitation of the BBC a quarter century after our original trips to research the Strip was fascinating for us. A comparison of Las Vegas in 1994 with what fifteen Yale students, Steven Izenour, and we found in 1968 and documented in Learning from Las Vegas in 1972 demonstrates a vivid and significant evolution, urban and architectural - perhaps comparable to returning to Florence a century after the quattrocento?"

"Though it is difficult for architects to believe, this study emanated as well from the social planning movement of the 1960s and the admonitions to architects by Gans, Jane Jacobs, and others to be more open to values other that their own and less quick to apply personal norms to societal problems - to be part, as we used to say, of the solution rather than the problem. People ‘voted with their feet' by going to Las Vegas; architects, the social planners suggested, should hold their disdain for its visual environment long enough, at least, to discover why people liked it. Our study was part of a broader attempt to find ways to place our architectural talents at the service of our social ideals."

"The Strip has seen a considerable reduction in the number and size of its signs and a parallel evolution from signography to scenography, or from the decorated shed to the duck. [...]"

VENTURI, Robert; SCOTT BROWN, Denise. Las Vegas after its classical age. In: VENTURI, Robert. Iconography and electronics upon a generic architecture: a view from the drafting room. Cambridge; Londres: The MIT Press, 1996. p. 123-128.

"Denise Scott Brown (one of the Smithsons' ambivalent heirs) and Robert Venturi break even more definitively with modernist dogma in their advocacy of consumerist culture. In their publications, exhibitions, and teachings of the 1970s (most notably, Learning from Las Vegas and the Smithsonian Institution exhibition Signs of Life), they allude to a world neglected in both modern architecture and Foucault's heterotopic landscape: the A & P supermarket, Levittown, mobile homes, fast-food stores - the milieu of ordinary middle- and lower-class people [...]. Learning from La Vegas does contain an overdose of honeymoon motels and gambling casinos, but in contrast to Foucault's heterotopic spaces or Anthony Vidler's examples of the uncanny, this landscape is not privileged for its difference or strangeness but taken as part of continuum of daily existence. Like the Independent Group, Scott Brown and Venturi grant the world of women, children, and elderly people - domestic culture - a place in aesthetic culture. [...]"

McLEOD, Mary. Everyday and "Other" Spaces. In: COLEMAN, Debra; DANZE, Elisabeth; HENDERSON, Carol (Ed.). Architecture and feminism. Nova York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996. p. 1-37, grifos da autora.

"RK: Recently we have been comparing Las Vegas as it was in 1972 and as it is now in 2000, as a response to both the methods and conclusion of your book. When you look at the change in scale of the city between these two dates, not only in terms of area but in other categories like population, births, marriages, personal income, hotel rooms, etc., the development is unbelievable: the archetype of unreality - the city-as-mirage you described in Learning from Las Vegas - has, through sheer mass, become a real city. So Las Vegas seems to be one of the few cities to become paradigmatic twice in thirty years: from a city at the point of becoming virtual in 1972 to an almost irrevocably substantial condition in 2000.

Denise Scott Brown: Three times, if you start with the desert and say forty years. Most cities change paradigms - many European cities began as Roman camps, then became Medieval towns, and eventually modern cities.

RV: Yes, but that is over centuries, not in the course of decades. [But] when we were interested in Las Vegas twenty-five years ago, when it represented iconographic sprawl, our interest was clearly daring. This is hard to believe today because Las Vegas has become scenographic like Disneyland.

RK: But isn't it still daring? One of the paradoxes of Las Vegas is that in spite of its thirty years, it's still not taken seriously.

HUO: Is it still a taboo to take Las Vegas seriously?

DSB: The critics seem to take the present Las Vegas more seriously that they did the 1960s Las Vegas."

SCOT BROWN, Denise; VENTURI, Robert; OBRIST, Hans Ulrich; KOOLHAAS, Rem. Re-Learning from Las Vegas. In: CHUNG, Chuihua Judy et al. (Ed.).The Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping. Köln: Taschen, 2001. p. 590-617, grifos dos autores. Col. Project on the City, v. 2.

"Rauterberg Are you learning from any of today's artists?

Venturi Jenny Holzer, perhaps. Though her work seems a little too correct to me, they don't have any of that beautiful, vital vulgarity of commercial art. Too pure for us; we're for the impure.

Scott Brown That's why we set off for Las Vegas in the 1960s: to find out what models architecture followed there, how it worked, how it was applied. Las Vegas buildings didn't dabble in artistry, didn't dream of a better world; they were bound to reality and its laws. We didn't go to Las Vegas to submit to its architecture but to try to understand it - to learn how it interprets people's longings and finds an architectural response to them.

Venturi Yes, that was one reason. The other was that through our excursion to Las Vegas we wanted to emancipate ourselves from the dogmas of the Modern."

VENTURI, Robert; SCOTT BROWN, Denise; RAUTERBERG, Hanno. We're for the impure: Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown talk with Hanno Rautenberg. Hunch, Rotterdam, n. 6/7, p. 460-461, 2003.

"One deleterious outcome of interpreting Learning from Las Vegas as simply a postmodern text has been its exposure to a particular kind of Adornian criticism. [...] In essence, these accounts of Learning from Las Vegas posit that the book exemplifies an ironic toleration and passive acceptance, even an unabashed embrace, of the culture industry. This species of criticism emerged almost immediately after the book was published, and continues to be the dominant mode of criticism of it to the present day. [...]

A strict adherence to critical theory-based interpretation obscures the subtle aversive criticism that Learning from Las Vegas demonstrates, and which can easily be misinterpreted as uncritical collusion with the culture industry. [...] In other words, the book is much more critically and ethically charged than has previously been assumed. [...]"

VINEGAR, Aron. I am a monument: on Learning from Las Vegas. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2008, grifos do autor.

Projeto

Projeto Publicaçăo

Publicaçăo Evento

Evento Fato Relevante

Fato Relevante